Pacific Ocean

| Pacific Ocean | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 0°N 160°W / 0°N 160°W |

| Surface area | 165,250,000 km2 (63,800,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 4,280 m (14,040 ft) |

| Max. depth | 10,911 m (35,797 ft) |

| Water volume | 710,000,000 km3 (170,000,000 cu mi) |

| Islands | Pacific Islands |

| Settlements | List |

| Earth's ocean |

|---|

|

Main five oceans division: Further subdivision: Marginal seas |

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continents of Asia and Australia in the west and the Americas in the east.

At 165,250,000 square kilometers (63,800,000 square miles) in area (as defined with a southern Antarctic border), the largest division of the World Ocean and the hydrosphere covers about 46% of Earth's water surface and about 32% of the planet's total surface area, larger than its entire land area (148,000,000 km2 (57,000,000 sq mi)).[1] The centers of both the water hemisphere and the Western Hemisphere, as well as the oceanic pole of inaccessibility, are in the Pacific Ocean. Ocean circulation (caused by the Coriolis effect) subdivides it[2] into two largely independent volumes of water that meet at the equator, the North Pacific Ocean and the South Pacific Ocean (or more loosely the South Seas). The Pacific Ocean can also be informally divided by the International Date Line into the East Pacific and the West Pacific, which allows it to be further divided into four quadrants, namely the Northeast Pacific off the coasts of North America, the Southeast Pacific off South America, the Northwest Pacific off Far Eastern/Pacific Asia, and the Southwest Pacific around Oceania.

The Pacific Ocean's mean depth is 4,000 meters (13,000 feet).[3] The Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, located in the northwestern Pacific, is the deepest known point in the world, reaching a depth of 10,928 meters (35,853 feet).[4] The Pacific also contains the deepest point in the Southern Hemisphere, the Horizon Deep in the Tonga Trench, at 10,823 meters (35,509 feet).[5] The third deepest point on Earth, the Sirena Deep, is also located in the Mariana Trench.

The western Pacific has many major marginal seas, including the Philippine Sea, South China Sea, East China Sea, Sea of Japan, Sea of Okhotsk, Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska, Gulf of California, Mar de Grau, Tasman Sea, and the Coral Sea.

Etymology

[edit]In the early 16th century, Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama in 1513 and sighted the great "Southern Sea", which he named Mar del Sur (in Spanish). Afterwards, the ocean's current name was coined by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan during the Spanish circumnavigation of the world in 1521, as he encountered favorable winds upon reaching the ocean. He called it Mar Pacífico, which in Portuguese means 'peaceful sea'.[6][7]

Seas in the Pacific Ocean

[edit]

Top large seas:[8]

- Australasian Mediterranean Sea – 9.080 million km2 (includes other seas)

- Philippine Sea – 5.695 million km2 (largest single sea)

- Coral Sea – 4.791 million km2

- Chilean Sea – 3.6 million km2

- South China Sea – 3.5 million km2

- Tasman Sea – 2.3 million km2

- Bering Sea – 2 million km2

- Sea of Okhotsk – 1.583 million km2

- Gulf of Alaska – 1.533 million km2

- East China Sea – 1.249 million km2

- Mar de Grau – 1.14 million km2

- Sea of Japan – 978,000 km2

- Solomon Sea – 720,000 km2

- Banda Sea – 695,000 km2

- Arafura Sea – 650,000 km2

- Timor Sea – 610,000 km2

- Yellow Sea – 380,000 km2

- Java Sea – 320,000 km2

- Gulf of Thailand – 320,000 km2

- Gulf of Carpentaria – 300,000 km2

- Celebes Sea – 280,000 km2

- Sulu Sea – 260,000 km2

- Bismarck Sea – 250,400 km2

- Gulf of Anadyr – 200,000 km2

- Molucca Sea – 200,000 km2

- Gulf of California – 160,000 km2

- Gulf of Tonkin – 126,250 km2

- Halmahera Sea – 95,000 km2

- Bohai Sea – 78,000 km2

- Gulf of Papua – 70,400 km2

- Koro Sea – 58,000 km2

- Bali Sea – 45,000 km2

- Savu Sea – 35,000 km2

- Seto Inland Sea – 23,203 km2

- Salish Sea – 18,000 km2

- Seram Sea – 12,000 km2

- Shelikhov Gulf – 1,583,000 km2

- Laizhou Bay – 7,000 km2

- Manila Bay – 1,994 km2

- Tayabas Bay – 2,500 km2

- Visayan Sea – 10,000 km2

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Across the continents of Asia, Australia and the Americas, more than 25,000 islands, large and small, rise above the surface of the Pacific Ocean. Multiple islands were the shells of former active volcanoes that have lain dormant for thousands of years. Close to the equator, without vast areas of blue ocean, are a dot of atolls that have over intervals of time been formed by seamounts as a result of tiny coral islands strung in a ring within surroundings of a central lagoon.

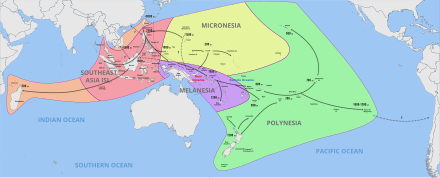

Early migrations

[edit]

Important human migrations occurred in the Pacific in prehistoric times. Modern humans first reached the western Pacific in the Paleolithic, at around 60,000 to 70,000 years ago. Originating from a southern coastal human migration out of Africa, they reached East Asia, Mainland Southeast Asia, the Philippines, New Guinea, and then Australia by making the sea crossing of at least 80 kilometres (50 mi) between Sundaland and Sahul. It is not known with any certainty what level of maritime technology was used by these groups – the presumption is that they used large bamboo rafts which may have been equipped with some sort of sail. The reduction in favourable winds for a crossing to Sahul after 58,000 B.P. fits with the dating of the settlement of Australia, with no later migrations in the prehistoric period. The seafaring abilities of pre-Austronesian residents of Island South-east Asia are confirmed by the settlement of Buka by 32,000 B.P. and Manus by 25,000 B.P. Journeys of 180 kilometres (110 mi) and 230 kilometres (140 mi) are involved, respectively.[9]

The descendants of these migrations today are the Negritos, Melanesians, and Indigenous Australians. Their populations in maritime Southeast Asia, coastal New Guinea, and Island Melanesia later intermarried with the incoming Austronesian settlers from Taiwan and the northern Philippines, but also earlier groups associated with Austroasiatic-speakers, resulting in the modern peoples of Island Southeast Asia and Oceania.[10][11]

A later seaborne migration is the Neolithic Austronesian expansion of the Austronesian peoples. Austronesians originated from the island of Taiwan c. 3000–1500 BCE. They are associated with distinctive maritime sailing technologies (notably outrigger boats, catamarans, lashed-lug boats, and the crab claw sail) – it is likely that the progressive development of these technologies were related to the later steps of settlement into Near and Remote Oceania. Starting at around 2200 BCE, Austronesians sailed southwards to settle the Philippines. From, probably, the Bismarck Archipelago they crossed the western Pacific to reach the Marianas Islands by 1500 BCE,[12] as well as Palau and Yap by 1000 BCE. They were the first humans to reach Remote Oceania, and the first to cross vast distances of open water. They also continued spreading southwards and settling the rest of Maritime Southeast Asia, reaching Indonesia and Malaysia by 1500 BCE, and further west to Madagascar and the Comoros in the Indian Ocean by around 500 CE.[13][14][15] More recently, it is suggested that Austronesians expanded already earlier, arriving in the Philippines already in 7000 BCE. Additional earlier migrations into Insular Southeast Asia, associated with Austroasiatic-speakers from Mainland Southeast Asia, are estimated to have taken place already in 15000 BCE.[16]

At around 1300 to 1200 BCE, a branch of the Austronesian migrations known as the Lapita culture reached the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia. From there, they settled Tonga and Samoa by 900 to 800 BCE. Some also back-migrated northwards in 200 BCE to settle the islands of eastern Micronesia (including the Carolines, the Marshall Islands, and Kiribati), mixing with earlier Austronesian migrations in the region. This remained the furthest extent of the Austronesian expansion into Polynesia until around 700 CE when there was another surge of island exploration. They reached the Cook Islands, Tahiti, and the Marquesas by 700 CE; Hawaiʻi by 900 CE; Rapa Nui by 1000 CE; and finally New Zealand by 1200 CE.[14][17][18] Austronesians may have also reached as far as the Americas, although evidence for this remains inconclusive.[19][20]

European exploration

[edit]

The first contact of European navigators with the western edge of the Pacific Ocean was made by the Portuguese expeditions of António de Abreu and Francisco Serrão, via the Lesser Sunda Islands, to the Maluku Islands, in 1512,[21][22] and with Jorge Álvares's expedition to southern China in 1513,[23] both ordered by Afonso de Albuquerque from Malacca.

The eastern side of the ocean was encountered by Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1513 after his expedition crossed the Isthmus of Panama and reached a new ocean.[24] He named it Mar del Sur ("Sea of the South" or "South Sea") because the ocean was to the south of the coast of the isthmus where he first observed the Pacific.

In 1520, navigator Ferdinand Magellan and his crew were the first to cross the Pacific in recorded history. They were part of a Spanish expedition to the Spice Islands that would eventually result in the first world circumnavigation. Magellan called the ocean Pacífico (or "Pacific" meaning, "peaceful") because, after sailing through the stormy seas off Cape Horn, the expedition found calm waters. The ocean was often called the Sea of Magellan in his honor until the eighteenth century.[25] Magellan stopped at one uninhabited Pacific island before stopping at Guam in March 1521.[26] Although Magellan himself died in the Philippines in 1521, Spanish navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano led the remains of the expedition back to Spain across the Indian Ocean and round the Cape of Good Hope, completing the first world circumnavigation in 1522.[27] Sailing around and east of the Moluccas, between 1525 and 1527, Portuguese expeditions encountered the Caroline Islands,[28] the Aru Islands,[29] and Papua New Guinea.[30] In 1542–43 the Portuguese also reached Japan.[31]

In 1564, five Spanish ships carrying 379 soldiers crossed the ocean from Mexico led by Miguel López de Legazpi, and colonized the Philippines and Mariana Islands.[32] For the remainder of the 16th century, Spain maintained military and mercantile control, with ships sailing from Mexico and Peru across the Pacific Ocean to the Philippines via Guam, and establishing the Spanish East Indies. The Manila galleons operated for two and a half centuries, linking Manila and Acapulco, in one of the longest trade routes in history. Spanish expeditions also arrived at Tuvalu, the Marquesas, the Cook Islands, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, the Marshalls and the Admiralty Islands in the South Pacific.[33]

Later, in the quest for Terra Australis ("the [great] Southern Land"), Spanish explorations in the 17th century, such as the expedition led by the Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, arrived at the Pitcairn and Vanuatu archipelagos, and sailed the Torres Strait between Australia and New Guinea, named after navigator Luís Vaz de Torres. Dutch explorers, sailing around southern Africa, also engaged in exploration and trade; Willem Janszoon, made the first completely documented European landing in Australia (1606), in Cape York Peninsula,[34] and Abel Janszoon Tasman circumnavigated and landed on parts of the Australian continental coast and arrived at Tasmania and New Zealand in 1642.[35]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Spain considered the Pacific Ocean a mare clausum – a sea closed to other naval powers. As the only known entrance from the Atlantic, the Strait of Magellan was at times patrolled by fleets sent to prevent the entrance of non-Spanish ships. On the western side of the Pacific Ocean the Dutch threatened the Spanish Philippines.[36]

The 18th century marked the beginning of major exploration by the Russians in Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, such as the First Kamchatka expedition and the Great Northern Expedition, led by the Danish-born Russian navy officer Vitus Bering. Spain also sent expeditions to the Pacific Northwest, reaching Vancouver Island in southern Canada, and Alaska. The French explored and colonized Polynesia, and the British made three voyages with James Cook to the South Pacific and Australia, Hawaii, and the North American Pacific Northwest. In 1768, Pierre-Antoine Véron, a young astronomer accompanying Louis Antoine de Bougainville on his voyage of exploration, established the width of the Pacific with precision for the first time in history.[37] One of the earliest voyages of scientific exploration was organized by Spain in the Malaspina Expedition of 1789–1794. It sailed vast areas of the Pacific, from Cape Horn to Alaska, Guam and the Philippines, New Zealand, Australia, and the South Pacific.[33]

-

Made in 1529, the Diogo Ribeiro map was the first to show the Pacific at about its proper size

-

Map of the Pacific Ocean during European Exploration, circa 1754.

-

Map of the Pacific Ocean during European Exploration, circa 1702–1707

New Imperialism

[edit]

Growing imperialism during the 19th century resulted in the occupation of much of Oceania by European powers, and later Japan and the United States. Significant contributions to oceanographic knowledge were made by the voyages of HMS Beagle in the 1830s, with Charles Darwin aboard;[39] HMS Challenger during the 1870s;[40] the USS Tuscarora (1873–76);[41] and the German Gazelle (1874–76).[42]

In Oceania, France obtained a leading position as imperial power after making Tahiti and New Caledonia protectorates in 1842 and 1853, respectively.[43] After navy visits to Easter Island in 1875 and 1887, Chilean navy officer Policarpo Toro negotiated the incorporation of the island into Chile with native Rapanui in 1888. By occupying Easter Island, Chile joined the imperial nations.[44]: 53 By 1900 nearly all Pacific islands were in control of Britain, France, United States, Germany, Japan, and Chile.[43]

Although the United States gained control of Guam and the Philippines from Spain in 1898,[45] Japan controlled most of the western Pacific by 1914 and occupied many other islands during the Pacific War; however, by the end of that war, Japan was defeated and the U.S. Pacific Fleet was the virtual master of the ocean. The Japanese-ruled Northern Mariana Islands came under the control of the United States.[46] Since the end of World War II, many former colonies in the Pacific have become independent states.

Geography

[edit]

The Pacific separates Asia and Australia from the Americas. It may be further subdivided by the equator into northern (North Pacific) and southern (South Pacific) portions. It extends from the Antarctic region in the South to the Arctic in the north.[1] The Pacific Ocean encompasses approximately one-third of the Earth's surface, having an area of 165,200,000 km2 (63,800,000 sq mi) – larger than Earth's entire landmass combined, 150,000,000 km2 (58,000,000 sq mi).[47]

Extending approximately 15,500 km (9,600 mi) from the Bering Sea in the Arctic to the northern extent of the circumpolar Southern Ocean at 60°S (older definitions extend it to Antarctica's Ross Sea), the Pacific reaches its greatest east–west width at about 5°N latitude, where it stretches approximately 19,800 km (12,300 mi) from Indonesia to the coast of Colombia – halfway around the world, and more than five times the diameter of the Moon.[48] Its geographic center is in eastern Kiribati south of Kiritimati, just west from Starbuck Island at 4°58′S 158°45′W / 4.97°S 158.75°W.[49] The lowest known point on Earth – the Mariana Trench – lies 10,911 m (35,797 ft; 5,966 fathoms) below sea level. Its average depth is 4,280 m (14,040 ft; 2,340 fathoms), putting the total water volume at roughly 710,000,000 km3 (170,000,000 cu mi).[1]

Due to the effects of plate tectonics, the Pacific Ocean is currently shrinking by roughly 2.5 cm (1 in) per year on three sides, roughly averaging 0.52 km2 (0.20 sq mi) a year. By contrast, the Atlantic Ocean is increasing in size.[50][51]

Along the Pacific Ocean's irregular western margins lie many seas, the largest of which are the Celebes Sea, Coral Sea, East China Sea (East Sea), Philippine Sea, Sea of Japan, South China Sea (South Sea), Sulu Sea, Tasman Sea, and Yellow Sea (West Sea of Korea). The Indonesian Seaway (including the Strait of Malacca and Torres Strait) joins the Pacific and the Indian Ocean to the west, and Drake Passage and the Strait of Magellan link the Pacific with the Atlantic Ocean on the east. To the north, the Bering Strait connects the Pacific with the Arctic Ocean.[52]

As the Pacific straddles the 180th meridian, the West Pacific (or western Pacific, near Asia) is in the Eastern Hemisphere, while the East Pacific (or eastern Pacific, near the Americas) is in the Western Hemisphere.[53]

The Southern Pacific Ocean harbors the Southeast Indian Ridge crossing from south of Australia turning into the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge (north of the South Pole) and merges with another ridge (south of South America) to form the East Pacific Rise which also connects with another ridge (south of North America) which overlooks the Juan de Fuca Ridge.

For most of Magellan's voyage from the Strait of Magellan to the Philippines, the explorer indeed found the ocean peaceful; however, the Pacific is not always peaceful. Many tropical storms batter the islands of the Pacific.[54] The lands around the Pacific Rim are full of volcanoes and often affected by earthquakes.[55] Tsunamis, caused by underwater earthquakes, have devastated many islands and in some cases destroyed entire towns.[56]

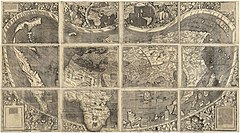

The Martin Waldseemüller map of 1507 was the first to show the Americas separating two distinct oceans.[57] Later, the Diogo Ribeiro map of 1529 was the first to show the Pacific at about its proper size.[58]

Bordering countries

[edit]

(Inhabited dependent territories are denoted by the asterisk (*), with names of the corresponding sovereign states in round brackets. Associated states in the Realm of New Zealand are denoted by the hash sign (#).)

Asia-Pacific

[edit] American Samoa* (US)

American Samoa* (US) Australia

Australia Brunei

Brunei Cambodia

Cambodia People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China Cook Islands #

Cook Islands # Federated States of Micronesia

Federated States of Micronesia Fiji

Fiji French Polynesia* (France)

French Polynesia* (France) Guam* (US)

Guam* (US) Hong Kong* (People's Republic of China)

Hong Kong* (People's Republic of China) Indonesia

Indonesia Japan

Japan Kiribati

Kiribati Macau* (People's Republic of China)

Macau* (People's Republic of China) Malaysia

Malaysia Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Nauru

Nauru New Caledonia* (France)

New Caledonia* (France) New Zealand

New Zealand Niue #

Niue # Norfolk Island* (Australia)

Norfolk Island* (Australia) Northern Mariana Islands* (US)

Northern Mariana Islands* (US) North Korea

North Korea Palau

Palau Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea Philippines

Philippines Pitcairn Islands* (UK)

Pitcairn Islands* (UK) Russia

Russia Samoa

Samoa Singapore

Singapore Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands South Korea

South Korea Taiwan

Taiwan Thailand

Thailand Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste Tonga

Tonga Tokelau* (New Zealand)

Tokelau* (New Zealand) Tuvalu

Tuvalu Vanuatu

Vanuatu Vietnam

Vietnam Wallis and Futuna* (France)

Wallis and Futuna* (France)

Americas

[edit]Uninhabited territories

[edit]Territories with no permanent civilian population.

Baker Island (US)

Baker Island (US) Clipperton Island (France)

Clipperton Island (France) Coral Sea Islands (Australia)

Coral Sea Islands (Australia) Howland Island (US)

Howland Island (US) Jarvis Island (US)

Jarvis Island (US) Johnston Island (US)

Johnston Island (US) Kingman Reef (US)

Kingman Reef (US) Macquarie Island (Australia)

Macquarie Island (Australia) Midway Atoll (US)

Midway Atoll (US) Palmyra Atoll (US)

Palmyra Atoll (US) Wake Island (US)

Wake Island (US)

Landmasses and islands

[edit]

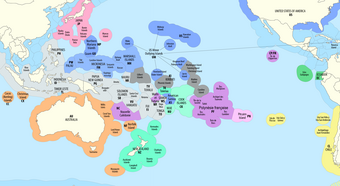

The Pacific Ocean has most of the islands in the world. There are about 25,000 islands in the Pacific Ocean.[59][60][61] The islands entirely within the Pacific Ocean can be divided into three main groups known as Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia. Micronesia, which lies north of the equator and west of the International Date Line, includes the Mariana Islands in the northwest, the Caroline Islands in the center, the Marshall Islands to the east and the islands of Kiribati in the southeast.[62][63]

Melanesia, to the southwest, includes New Guinea, the world's second largest island after Greenland and by far the largest of the Pacific islands. The other main Melanesian groups from north to south are the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, Santa Cruz, Vanuatu, Fiji and New Caledonia.[64]

The largest area, Polynesia, stretching from Hawaii in the north to New Zealand in the south, also encompasses Tuvalu, Tokelau, Samoa, Tonga and the Kermadec Islands to the west, the Cook Islands, Society Islands and Austral Islands in the center, and the Marquesas Islands, Tuamotu, Mangareva Islands, and Easter Island to the east.[65]

Islands in the Pacific Ocean are of four basic types: continental islands, high islands, coral reefs and uplifted coral platforms. Continental islands lie outside the andesite line and include New Guinea, the islands of New Zealand, and the Philippines. Some of these islands are structurally associated with nearby continents. High islands are of volcanic origin, and many contain active volcanoes. Among these are Bougainville, Hawaii, and the Solomon Islands.[66]

The coral reefs of the South Pacific are low-lying structures that have built up on basaltic lava flows under the ocean's surface. One of the most dramatic is the Great Barrier Reef off northeastern Australia with chains of reef patches. A second island type formed of coral is the uplifted coral platform, which is usually slightly larger than the low coral islands. Examples include Banaba (formerly Ocean Island) and Makatea in the Tuamotu group of French Polynesia.[67][68]

-

Ladrilleros Beach in Colombia on the coast of Chocó natural region

-

Tahuna maru islet, French Polynesia

-

Los Molinos on the coast of Southern Chile

Flora and fauna

See also: "Fauna of the Pacific" category

The Pacific Ocean accounts for more than 50% of the total biomass of the World Ocean. Life in the ocean is abundant and diverse, especially in the tropical and subtropical zones between the coasts of Asia and Australia, where coral reefs and mangroves dominate. Phytoplankton of the Pacific Ocean consists mainly of microscopic single-celled algae, numbering about 1,300. About half of the species belong to peridins and a little less to diatoms. Shallow areas and upwelling zones contain most of the vegetation. The bottom vegetation of the Pacific Ocean includes approximately 4,000 species of algae and up to 29 species of flowering plants. In the temperate and cold regions of the Pacific Ocean, brown algae, especially from the Laminaria group, are widespread, and in the southern hemisphere, from this family, up to 200 m long, in the tropics, fucus, large green and well-. certain red algae are particularly common and are reef-building organisms along with coral polyps [23].

Water characteristics

[edit]

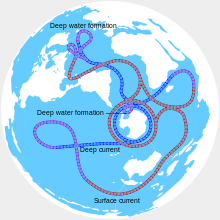

The volume of the Pacific Ocean, representing about 50.1 percent of the world's oceanic water, has been estimated at some 714 million cubic kilometers (171 million cubic miles).[69] Surface water temperatures in the Pacific can vary from −1.4 °C (29.5 °F), the freezing point of seawater, in the poleward areas to about 30 °C (86 °F) near the equator.[70] Salinity also varies latitudinally, reaching a maximum of 37 parts per thousand in the southeastern area. The water near the equator, which can have a salinity as low as 34 parts per thousand, is less salty than that found in the mid-latitudes because of abundant equatorial precipitation throughout the year. The lowest counts of less than 32 parts per thousand are found in the far north as less evaporation of seawater takes place in these frigid areas.[71] The motion of Pacific waters is generally clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere (the North Pacific gyre) and counter-clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. The North Equatorial Current, driven westward along latitude 15°N by the trade winds, turns north near the Philippines to become the warm Japan or Kuroshio Current.[72]

Turning eastward at about 45°N, the Kuroshio forks and some water moves northward as the Aleutian Current, while the rest turns southward to rejoin the North Equatorial Current.[73] The Aleutian Current branches as it approaches North America and forms the base of a counter-clockwise circulation in the Bering Sea. Its southern arm becomes the chilled slow, south-flowing California Current.[74] The South Equatorial Current, flowing west along the equator, swings southward east of New Guinea, turns east at about 50°S, and joins the main westerly circulation of the South Pacific, which includes the Earth-circling Antarctic Circumpolar Current. As it approaches the Chilean coast, the South Equatorial Current divides; one branch flows around Cape Horn and the other turns north to form the Peru or Humboldt Current.[75]

Climate

[edit]

The climate patterns of the Northern and Southern Hemispheres generally mirror each other. The trade winds in the southern and eastern Pacific are remarkably steady while conditions in the North Pacific are far more varied with, for example, cold winter temperatures on the east coast of Russia contrasting with the milder weather off British Columbia during the winter months due to the preferred flow of ocean currents.[76]

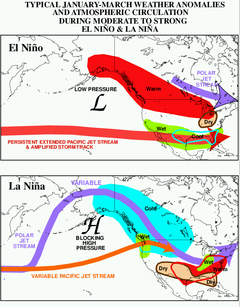

In the tropical and subtropical Pacific, the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) affects weather conditions. To determine the phase of ENSO, the most recent three-month sea surface temperature average for the area approximately 3,000 km (1,900 mi) to the southeast of Hawaii is computed, and if the region is more than 0.5 °C (0.9 °F) above or below normal for that period, then an El Niño or La Niña is considered in progress.[77]

In the tropical western Pacific, the monsoon and the related wet season during the summer months contrast with dry winds in the winter which blow over the ocean from the Asian landmass.[78] Worldwide, tropical cyclone activity peaks in late summer, when the difference between temperatures aloft and sea surface temperatures is the greatest; however, each particular basin has its own seasonal patterns. On a worldwide scale, May is the least active month, while September is the most active month. November is the only month in which all the tropical cyclone basins are active.[79] The Pacific hosts the two most active tropical cyclone basins, which are the northwestern Pacific and the eastern Pacific. Pacific hurricanes form south of Mexico, sometimes striking the western Mexican coast and occasionally the Southwestern United States between June and October, while typhoons forming in the northwestern Pacific moving into southeast and east Asia from May to December. Tropical cyclones also form in the South Pacific basin, where they occasionally impact island nations.[80]

In the arctic, icing from October to May can present a hazard for shipping while persistent fog occurs from June to December.[81] A climatological low in the Gulf of Alaska keeps the southern coast wet and mild during the winter months. The Westerlies and associated jet stream within the Mid-Latitudes can be particularly strong, especially in the Southern Hemisphere, due to the temperature difference between the tropics and Antarctica,[82] which records the coldest temperature readings on the planet. In the Southern hemisphere, because of the stormy and cloudy conditions associated with extratropical cyclones riding the jet stream, it is usual to refer to the Westerlies as the Roaring Forties, Furious Fifties and Shrieking Sixties according to the varying degrees of latitude.[83]

Geology

[edit]

The ocean was first mapped by Abraham Ortelius; he called it Maris Pacifici following Ferdinand Magellan's description of it as "a pacific sea" during his circumnavigation from 1519 to 1522. To Magellan, it seemed much more calm (pacific) than the Atlantic.[84]

The andesite line is the most significant regional distinction in the Pacific. A petrologic boundary, it separates the deeper, mafic igneous rock of the Central Pacific Basin from the partially submerged continental areas of felsic igneous rock on its margins.[85] The andesite line follows the western edge of the islands off California and passes south of the Aleutian arc, along the eastern edge of the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Kuril Islands, Japan, the Mariana Islands, the Solomon Islands, and New Zealand's North Island.[86][87]

The dissimilarity continues northeastward along the western edge of the Andes Cordillera along South America to Mexico, returning then to the islands off California. Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan, New Guinea, and New Zealand lie outside the andesite line.

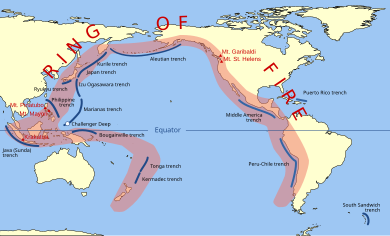

Within the closed loop of the andesite line are most of the deep troughs, submerged volcanic mountains, and oceanic volcanic islands that characterize the Pacific basin. Here basaltic lavas gently flow out of rifts to build huge dome-shaped volcanic mountains whose eroded summits form island arcs, chains, and clusters. Outside the andesite line, volcanism is of the explosive type, and the Pacific Ring of Fire is the world's foremost belt of explosive volcanism.[62] The Ring of Fire is named after the several hundred active volcanoes that sit above the various subduction zones.

The Pacific Ocean is the only ocean which is mostly bounded by subduction zones. Only the central part of the North American coast and the Antarctic and Australian coasts have no nearby subduction zones.

Geological history

[edit]The Pacific Ocean was born 750 million years ago at the breakup of Rodinia, although it is generally called the Panthalassa until the breakup of Pangea, about 200 million years ago.[88] The oldest Pacific Ocean floor is only around 180 Ma old, with older crust subducted by now.[89]

Seamount chains

[edit]The Pacific Ocean contains several long seamount chains, formed by hotspot volcanism. These include the Hawaiian–Emperor seamount chain and the Louisville Ridge.

Economy

[edit]The exploitation of the Pacific's mineral wealth is hampered by the ocean's great depths. In shallow waters of the continental shelves off the coasts of Australia and New Zealand, petroleum and natural gas are extracted, and pearls are harvested along the coasts of Australia, Japan, Papua New Guinea, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Philippines, although in sharply declining volume in some cases.[90]

Fishing

[edit]Fish are an important economic asset in the Pacific. The shallower shoreline waters of the continents and the more temperate islands yield herring, salmon, sardines, snapper, swordfish, and tuna, as well as shellfish.[91] Overfishing has become a serious problem in some areas. Overfishing leads to depleted fish populations and closed fisheries, causing both economic and ecologic consequences.[92] For example, catches in the rich fishing grounds of the Okhotsk Sea off the Russian coast have been reduced by at least half since the 1990s as a result of overfishing.[93]

Environment

[edit]

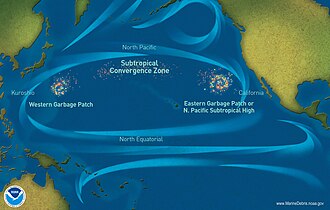

The Northwestern Pacific Ocean is most susceptible to micro plastic pollution due to its proximity to highly populated countries like Japan and China.[95] The quantity of small plastic fragments floating in the north-east Pacific Ocean increased a hundredfold between 1972 and 2012.[96] The ever-growing Great Pacific Garbage Patch between California and Japan is three times the size of France.[97] An estimated 80,000 metric tons of plastic inhabit the patch, totaling 1.8 trillion pieces.[98]

Marine pollution is a generic term for the harmful entry into the ocean of chemicals or particles. The main culprits are those using the rivers for disposing of their waste.[99] The rivers then empty into the ocean, often also bringing chemicals used as fertilizers in agriculture. The excess of oxygen-depleting chemicals in the water leads to hypoxia and the creation of a dead zone.[100]

Marine debris, also known as marine litter, is human-created waste that has ended up floating in a lake, sea, ocean, or waterway. Oceanic debris tends to accumulate at the center of gyres and coastlines, frequently washing aground where it is known as beach litter.[99]

In addition, the Pacific Ocean has served as the crash site of satellites, including Mars 96, Fobos-Grunt, and Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite.

Nuclear waste

[edit]

From 1946 to 1958, Marshall Islands served as the Pacific Proving Grounds, designated by the United States, and played host to a total of 67 nuclear tests conducted across various atolls.[102][103] Several nuclear weapons were lost in the Pacific Ocean,[104] including one-megaton bomb that was lost during the 1965 Philippine Sea A-4 incident.[105]

In 2021, the discharge of radioactive water from the Fukushima nuclear plant into the Pacific Ocean over a course of 30 years was approved by the Japanese Cabinet. The Cabinet concluded the radioactive water would have been diluted to drinkable standard.[106] Apart from dumping, leakage of tritium into the Pacific was estimated to be between 20 and 40 trillion Bqs from 2011 to 2013, according to the Fukushima plant.[107]

Deep sea mining

[edit]An emerging threat for the Pacific Ocean is the development of deep-sea mining. Deep-sea mining is aimed at extracting manganese nodules that contain minerals such as magnesium, nickel, copper, zinc and cobalt. The largest deposits of these are found in the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii in the Clarion Clipperton fracture zone.[108]

Deep-sea mining for manganese nodules appears to have drastic consequences for the ocean. It disrupts deep-sea ecosystems and may cause irreversible damage to fragile marine habitats.[109] Sediment stirring and chemical pollution threaten various marine animals. In addition, the mining process can lead to greenhouse gas emissions and promote further climate change. Preventing deep-sea mining is therefore important to ensure the long-term health of the ocean.[110]

Major ports and harbors

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2020) |

List of major ports

[edit]- Acapulco

- Auckland

- Bangkok

- Busan

- Callao

- Cebu City

- Dalian

- Guangzhou

- Haiphong

- Ho Chi Minh City

- Hong Kong

- Honolulu

- Jakarta

- Johor Bahru

- Kaohsiung

- Keelung

- Long Beach

- Los Angeles

- Manzanillo

- Manila

- Melbourne

- Nagoya

- Nakhodka

- Oakland

- Osaka

- Panama City

- Portland

- San Diego

- San Francisco

- Seattle

- Shanghai

- Singapore

- Sydney

- Tianjin

- Tokyo

- Valparaíso

- Vancouver

- Vladivostok

- Yokohama

List of seas, gulfs and bays by surface area

[edit]- Philippine Sea: 5,695,000 km2 (2,199,000 sq mi)

- Coral Sea: 4,791,000 km2 (1,850,000 sq mi)

- South China Sea: 3,500,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi)

- Tasman Sea: 2,300,000 km2 (890,000 sq mi)

- Bering Sea: 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi)

- Sea of Okhotsk: 1,583,000 km2 (611,000 sq mi)

- Gulf of Alaska: 1,533,000 km2 (592,000 sq mi)

- East China Sea: 1,249,000 km2 (482,000 sq mi)

- Sea of Japan: 978,000 km2 (378,000 sq mi)

- Solomon Sea: 720,000 km2 (280,000 sq mi)

- Arafura Sea: 650,000 km2 (250,000 sq mi)

- Banda Sea: 470,000 km2 (180,000 sq mi)

- Yellow Sea: 380,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi)

- Gulf of Thailand: 320,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi)

- Java Sea: 320,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi)

- Gulf of Carpentaria: 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi)

- Celebes Sea: 280,000 km2 (110,000 sq mi)

- Sulu Sea: 260,000 km2 (100,000 sq mi)

- Bismarck Sea: 250,400 km2 (96,700 sq mi)

- Flores Sea: 240,000 km2 (93,000 sq mi)

- Molucca Sea: 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi)

- Gulf of Anadyr: 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi)

- Gulf of California: 160,000 km2 (62,000 sq mi)

- Gulf of Tonkin: 126,250 km2 (48,750 sq mi)

- Halmahera Sea: 95,000 km2 (37,000 sq mi)

- Bohai Sea: 78,000 km2 (30,000 sq mi)

- Gulf of Papua: 70,400 km2 (27,200 sq mi)

- Koro Sea: 58,000 km2 (22,000 sq mi)

- Bali Sea: 45,000 km2 (17,000 sq mi)

- Savu Sea: 35,000 km2 (14,000 sq mi)

- Bohol Sea 29,000 km2 (11,000 sq mi)

- Seto Inland Sea: 23,203 km2 (8,959 sq mi)

- Sibuyan Sea 22,400 km2 (8,600 sq mi)

- Seram Sea 12,000 km (7,500 mi)

- Visayan Sea 11,850 km2 (4,580 sq mi)

- Gulf of Panama 2,400 km2 (930 sq mi)

- Manila Bay: 2,000 km2 (770 sq mi)

- Port Phillip: 1,930 km2 (750 sq mi)

- Tokyo Bay: 1,500 km2 (580 sq mi)

List of islands in the Pacific

[edit]Theories of natural delimitation between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans

[edit]

Scientific researchers have proposed delimiting the boundary between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans by two different natural boundaries, by the Shackleton fracture zone[111] and by the Scotia Arc[112][113][114] the former being more current than the latter.

See also

[edit]- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

- List of rivers of the Americas by coastline#Pacific Ocean coast

- Pacific Alliance

- Pacific coast

- Mikhail Tikhanov

- Pacific Time Zone

- Seven Seas

- Trans-Pacific Partnership

- War of the Pacific

- Natural delimitation between the Pacific and South Atlantic oceans by the Shackleton Fracture Zone

- Natural delimitation between the Pacific and South Atlantic oceans by the Scotia Arc

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Pacific Ocean". Britannica Concise. 2008: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ^ "The Coriolis Effect". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ "How big is the Pacific Ocean?". US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Deepest Submarine Dive in History, Five Deeps Expedition Conquers Challenger Deep" (PDF).

- ^ "CONFIRMED: Horizon Deep Second Deepest Point on the Planet" (PDF).

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ferdinand Magellan". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Ferdinand Magellan". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Evan Andrews (17 October 2023). "10 Surprising Facts About Magellan's Circumnavigation of the Globe". history.com. A&E Networks. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ "The Marginal Seas of the Pacific Ocean". World Atlas. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ O'Connor, Sue; Hiscock, Peter (2018). "The Peopling of Sahul and Near Oceania". In Cochrane, Ethan E; Hunt, Terry L. (eds.). The Oxford handbook of prehistoric Oceania. New York. ISBN 978-0199925070.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Jett, Stephen C. (2017). Ancient Ocean Crossings: Reconsidering the Case for Contacts with the Pre-Columbian Americas. University of Alabama Press. pp. 168–171. ISBN 978-0817319397. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Mahdi, Waruno (2017). "Pre-Austronesian Origins of Seafaring in Insular Southeast Asia". In Acri, Andrea; Blench, Roger; Landmann, Alexandra (eds.). Spirits and Ships: Cultural Transfers in Early Monsoon Asia. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. pp. 325–440. ISBN 978-9814762755. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Winter, Olaf; Clark, Geoffrey; Anderson, Atholl; Lindahl, Anders (September 2012). "Austronesian sailing to the northern Marianas, a comment on Hung et al. (2011)". Antiquity. 86 (333): 898–910. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00047992. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 161735451.

- ^ Heiske, Margit; Alva, Omar; Pereda-Loth, Veronica; Van Schalkwyk, Matthew; Radimilahy, Chantal; Letellier, Thierry; Rakotarisoa, Jean-Aimé; Pierron, Denis (22 January 2021). "Genetic evidence and historical theories of the Asian and African origins of the present Malagasy population". Human Molecular Genetics. 30 (R1): R72 – R78. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddab018. ISSN 0964-6906. PMID 33481023.

- ^ a b Gray RD, Drummond AJ, Greenhill SJ (January 2009). "Language phylogenies reveal expansion pulses and pauses in Pacific settlement". Science. 323 (5913): 479–483. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..479G. doi:10.1126/science.1166858. PMID 19164742. S2CID 29838345.

- ^ Pawley A (2002). "The Austronesian dispersal: languages, technologies and people". In Bellwood PS, Renfrew C (eds.). Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge. pp. 251–273. ISBN 978-1902937205.

- ^ Larena, Maximilian (22 March 2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (13): e2026132118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11826132L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512.

- ^ Stanley, David (2004). South Pacific. Avalon Travel. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-56691-411-6.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann. "'Game-changing' study suggests first Polynesians voyaged all the way from East Asia". Science. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- ^ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. 1994. Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press

- ^ Langdon, Robert. The Bamboo Raft as a Key to the Introduction of the Sweet Potato in Prehistoric Polynesia, The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 36, No. 1, 2001

- ^ Hannard, Willard A. (1991). Indonesian Banda: Colonialism and its Aftermath in the Nutmeg Islands. Bandanaira: Yayasan Warisan dan Budaya Banda Naira. p. 7.

- ^ Milton, Giles (1999). Nathaniel's Nutmeg. London: Sceptre. pp. 5, 7. ISBN 978-0-340-69676-7.

- ^ Porter, Jonathan. (1996). Macau, the Imaginary City: Culture and Society, 1557 to the Present. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3749-6

- ^ Ober, Frederick Albion (2010). Vasco Nuñez de Balboa. Library of Alexandria. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4655-7034-5.

- ^ Camino, Mercedes Maroto. Producing the Pacific: Maps and Narratives of Spanish Exploration (1567–1606), p. 76. 2005.

- ^ Guampedia entry on Ferdinand Magellan| url = https://www.guampedia.com/ferdinand-magellan/

- ^ "Life in the sea: Pacific Ocean", Oceanário de Lisboa. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ Galvano, Antonio (2004) [1563]. The Discoveries of the World from Their First Original Unto the Year of Our Lord 1555, issued by the Hakluyt Society. Kessinger Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-7661-9022-1.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kratoska, Paul H. (2001). South East Asia, Colonial History: Imperialism before 1800, Volume 1 de South East Asia, Colonial History. Taylor & Francis. pp. 52–56.[1]

- ^ Whiteway, Richard Stephen (1899). The rise of Portuguese power in India, 1497–1550. Westminster: A. Constable. p. 333.

- ^ Steven Thomas, "Portuguese in Japan". Steven's Balagan. 25 April 2006. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Henderson, James D.; Delpar, Helen; Brungardt, Maurice Philip; Weldon, Richard N. (2000). A Reference Guide to Latin American History. M.E. Sharpe. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-56324-744-6.

- ^ a b Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 305–307. ISBN 978-0-393-06259-5.

- ^ J.P. Sigmond and L.H. Zuiderbaan (1979) Dutch Discoveries of Australia.Rigby Ltd, Australia. pp. 19–30 ISBN 0-7270-0800-5

- ^ Primary Australian History: Book F [B6] Ages 10–11. R.I.C. Publications. 2008. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-74126-688-7.

- ^ Lytle Schurz, William (1922), "The Spanish Lake", The Hispanic American Historical Review, 5 (2): 181–194, doi:10.2307/2506024, JSTOR 2506024

- ^ Williams, Glyndwr (2004). Captain Cook: Explorations And Reassessments. Boydell Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-84383-100-6.

- ^ "Library Acquires Copy of 1507 Waldseemüller World Map – News Releases (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Marty, Christoph. "Charles Darwin's Travels on the HMS Beagle". Scientific American. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "The Voyage of HMS Challenger". interactiveoceans.washington.edu. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ A Synopsis of the Cruise of the U.S.S. "Tuscarora": From the Date of Her Commission to Her Arrival in San Francisco, Cal. Sept. 2d, 1874. Cosmopolitan printing Company. 1874.

- ^ Johnston, Keith (1881). "A Physical, Historical, Political, & Descriptive Geography". Nature. 22 (553): 95. Bibcode:1880Natur..22Q..95.. doi:10.1038/022095a0. S2CID 4070183.

- ^ a b Bernard Eccleston, Michael Dawson. 1998. The Asia-Pacific Profile. Routledge. p. 250.

- ^ William Sater, Chile and the United States: Empires in Conflict, 1990 by the University of Georgia Press, ISBN 0-8203-1249-5

- ^ Tewari, Nita; Alvarez, Alvin N. (2008). Asian American Psychology: Current Perspectives. CRC Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-84169-749-9.

- ^ The Covenant to Establish a Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in Political Union With the United States of America, Pub. L. 94–241, 90 Stat. 263, enacted March 24, 1976

- ^ "Area of Earth's Land Surface", The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ Nuttall, Mark (2005). Encyclopedia of the Arctic: A–F. Routledge. p. 1461. ISBN 978-1-57958-436-8.

- ^ "International Journal of Oceans and Oceanography, Volume 15 Number 1, 2021, Determining the Areas and Geographical Centers of Pacific Ocean and its Northern and Southern Halves, pp 25–31, Arjun Tan". Research India Publications. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Plate Tectonics". Bucknell University. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ Young, Greg (2009). Plate Tectonics. Capstone. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7565-4232-0.

- ^ International Hydrographic Organization (1953). "Limits of Oceans and Seas". Nature. 172 (4376): 484. Bibcode:1953Natur.172R.484.. doi:10.1038/172484b0. S2CID 36029611.

- ^ Agno, Lydia (1998). Basic Geography. Goodwill Trading Co., Inc. p. 25. ISBN 978-971-11-0165-7.

- ^ "Pacific Ocean: The trade winds", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ Shirley Rousseau Murphy (1979). The Ring of Fire. Avon. ISBN 978-0-380-47191-1.

- ^ Bryant, Edward (2008). Tsunami: The Underrated Hazard. Springer. p. 26. ISBN 978-3-540-74274-6.

- ^ "The Map That Named America". loc.gov. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Ribero, Diego, Carta universal en que se contiene todo lo que del mundo se ha descubierto fasta agora / hizola Diego Ribero cosmographo de su magestad, ano de 1529, e[n] Sevilla, W. Griggs, retrieved 30 September 2017

- ^ K, Harsh (19 March 2017). "This ocean has most of the islands in the world". Mysticalroads. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Ishihara, Masahide; Hoshino, Eiichi; Fujita, Yoko (2016). Self-determinable Development of Small Islands. Springer. p. 180. ISBN 978-981-10-0132-1.

- ^ United States. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council (2009). Toward an Ecosystem Approach for the Western Pacific Region: from Species-based Fishery Management Plans to Place-based Fishery Ecosystem Plans: Environmental Impact Statement. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University. p. 60.

- ^ a b Academic American encyclopedia. Grolier Incorporated. 1997. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7172-2068-7.

- ^ Lal, Brij Vilash; Fortune, Kate (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8248-2265-1.

- ^ West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 521. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ^ Dunford, Betty; Ridgell, Reilly (1996). Pacific Neighbors: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. Bess Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-57306-022-6.

- ^ Gillespie, Rosemary G.; Clague, David A. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islands. University of California Press. p. 706. ISBN 978-0-520-25649-1.

- ^ "Coral island", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Nauru". Charting the Pacific. ABC Radio Australia. 2005.

- ^ "PWLF.org – The Pacific WildLife Foundation – The Pacific Ocean". Archived from the original on 21 April 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ Mongillo, John F. (2000). Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. University Rochester Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-57356-147-1.

- ^ "Pacific Ocean: Salinity", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Wind Driven Surface Currents: Equatorial Currents Background", Ocean Motion. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Kuroshio", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Aleutian Current", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "South Equatorial Current", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Pacific Ocean: Islands", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Climate Prediction Center (30 June 2014). "ENSO: Recent Evolution, Current Status and Predictions" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 5, 19–20. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Monsoon. Archived 22 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 16 January 2009.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory – Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: When is hurricane season?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 July 2006.

- ^ Chand, Savin S.; Dowdy, Andrew; Bell, Samuel; Tory, Kevin (2020), Kumar, Lalit (ed.), "A Review of South Pacific Tropical Cyclones: Impacts of Natural Climate Variability and Climate Change", Climate Change and Impacts in the Pacific, Springer Climate, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 251–273, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-32878-8_6, ISBN 978-3-030-32878-8, S2CID 212780026, retrieved 25 October 2023

- ^ "Pacific Ocean", World Factbook, CIA. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ John P. Stimac. Air pressure and wind. Retrieved on 8 May 2008.

- ^ Walker, Stuart (1998). The sailor's wind. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-393-04555-0.

- ^ Turnbull, Alexander (2006). Map New Zealand: 100 Magnificent Maps from the Collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library. Godwit. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-86962-126-1.

- ^ Trent, D. D.; Hazlett, Richard; Bierman, Paul (2010). Geology and the Environment. Cengage Learning. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-538-73755-5.

- ^ Lal, Brij Vilash; Fortune, Kate (2000). The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8248-2265-1.

- ^ Mueller-Dombois, Dieter (1998). Vegetation of the Tropical Pacific Islands. Springer. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-387-98313-4.

- ^ "GEOL 102 The Proterozoic Eon II: Rodinia and Pannotia". Geol.umd.edu. 5 January 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Mussett, Alan E.; Khan, M. Aftab (2000). Looking into the Earth: An Introduction to Geological Geophysics. Cambridge University Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-521-78574-7.

- ^ "Pacific Ocean: Fisheries", Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "Pacific Ocean: Commerce and Shipping", The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th edition. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Burgess, Matthew G (16 September 2013). "Predicting overfishing and extinction threats in multispecies fisheries". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (40): 15943–15948. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11015943B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314472110. PMC 3791778. PMID 24043810.

- ^ "Pacific Ocean Threats & Impacts: Overfishing and Exploitation" Archived 12 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Ocean Solutions. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Marine Debris Division – Office of Response and Restoration. NOAA. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014.

- ^ Pan, Zhong; Liu, Qianlong; Sun, Yan; Sun, Xiuwu; Lin, Hui (1 September 2019). "Environmental implications of microplastic pollution in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 146: 215–224. Bibcode:2019MarPB.146..215P. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.06.031. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 31426149. S2CID 196691104.

- ^ Plastic waste in the North Pacific is an ongoing concern BBC 9 May 2012

- ^ "'Great Pacific Garbage Patch' is massive floating island of plastic, now 3 times the size of France". United States: ABC News. 23 March 2018.

- ^ "'Great Pacific garbage patch' 16 times bigger than previously thought, say scientists". The Independent. 23 March 2018. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022.

- ^ a b Handwerk, Brian (4 September 2009). "Photos: Giant Ocean-Trash Vortex Documented – A First". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010.

- ^ Gerlach, Sebastian A. (1975). Marine Pollution (in German). Berlin: Springer.

- ^ 大月規義 (3 November 2020). "原発の処理水、菅首相「飲んでもいい?」 東電の説明は" [Prime Minister Suga asks if the treated radioactive water is drinkable. Here is TEPCO's response]. The Asahi Shimbun.

- ^ "Marshall Islands marks 71 years since start of US nuclear tests on Bikini". Radio New Zealand. 1 March 2017.

- ^ Lewis, Renee (28 July 2015). "Bikinians evacuated 'for good of mankind' endure lengthy nuclear fallout". Al Jazeera.

- ^ Thaler, Andrew David (26 July 2018). "How many nuclear weapons are at the bottom of the sea. An (almost certainly incomplete) census of broken arrows over water". Southern Fried Science.

- ^ Richard Halloran (26 May 1981). "U.S. discloses accidents involving nuclear weapons". The New York Times.

- ^ "Fukushima: Japan approves releasing wastewater into ocean". BBC. 13 April 2021.

- ^ Hsu, Jeremy (13 August 2013). "Radioactive Water Leaks from Fukushima: What We Know". Scientific American.

- ^ 'PEW – The Clarion-Clipperton Zone – Valuable minerals and many unusual species can be found on the eastern Pacific Ocean seafloor'

- ^ Jochen Halfar, Rodney M. Fujita (2007). "Danger of Deep-Sea Mining". Science. 316 (5827): 987. doi:10.1126/science.1138289. PMID 17510349. Archived from the original on 21 June 2021.

- ^ "Impacts of mining deep sea polymetallic nodules in the Pacific Ocean | Deep Sea Mining: Out of Our Depth". Archived from the original on 3 June 2020.

- ^ Juan Ignacio Ipinza Mayor; Cedomir Marangunic Damianovic (2021). "Algunas Consecuencias Jurídicas De La Invocación Por Parte De Chile De La "Teoría De La Delimitación Natural De Los Océanos" En El Diferendo Sobre La Plataforma Continental Austral". ANEPE (in Spanish).

- ^ Barros González, Guillermo (1987). "El Arco de Scotia, separación natural de los océanos Pacífico y Atlántico" (PDF). Revista de Marina (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Passarelli, Bruno (1998). El delirio armado: Argentina-Chile, la guerra que evitó el Papa (in Spanish). Editorial Sudamericana. p. 48. ISBN 978-9-5007-1469-3.

- ^ Santibañez, Rafael (1969). "El Canal Beagle y la delimitación de los océanos". Los derechos de Chile en el Beagle (in Spanish). Santiago: Editorial Andrés Bello. pp. 95–109. OCLC 1611130. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Barkley, Richard A. (1968). Oceanographic Atlas of the Pacific Ocean. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- prepared by the Special Publications Division, National Geographic Society. (1985). Blue Horizons: Paradise Isles of the Pacific. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-0-87044-544-6.

- Cameron, Ian (1987). Lost Paradise: The Exploration of the Pacific. Topsfield, MA: Salem House. ISBN 978-0-88162-275-1.

- Couper, A.D., ed. (1989). Development and Social Change in the Pacific Islands. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-00917-1.

- Gilbert, John (1971). Charting the Vast Pacific. London: Aldus. ISBN 978-0-490-00226-5.

- Igler, David (2013). The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-991495-1.

- Jones, Eric, Lionel Frost, and Colin White. Coming Full Circle: An Economic History of the Pacific Rim (Westview Press, 1993)

- Lower, J. Arthur (1978). Ocean of Destiny: A Concise History of the North Pacific, 1500–1978. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0101-0.

- Napier, W.; Gilbert, J.; Holland, J. (1973). Pacific Voyages. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-04335-9.

- Nunn, Patrick D. (1998). Pacific Island Landscapes: Landscape and Geological Development of Southwest Pacific Islands, Especially Fiji, Samoa and Tonga. editorips@usp.ac.fj. ISBN 978-982-02-0129-3.

- Oliver, Douglas L. (1989). The Pacific Islands (3rd ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1233-1.

- Paine, Lincoln. The Sea and Civilization: A Maritime History of the World (2015).

- Ridgell, Reilly (1988). Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia (2nd ed.). Honolulu: Bess Press. ISBN 978-0-935848-50-2.

- Samson, Jane. British imperial strategies in the Pacific, 1750–1900 (Ashgate Publishing, 2003).

- Soule, Gardner (1970). The Greatest Depths: Probing the Seas to 20,000 feet (6,100 m) and Below. Philadelphia: Macrae Smith. ISBN 978-0-8255-8350-6.

- Spate, O.H.K. (1988). Paradise Found and Lost. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1715-9.

- Terrell, John (1986). Prehistory in the Pacific Islands: A Study of Variation in Language, Customs, and Human Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30604-1.

Historiography

[edit]- Calder, Alex, et al. eds. Voyages and Beaches: Pacific Encounters, 1769–1840 (U of Hawai'i Press, 1999)

- Davidson, James Wightman. "Problems of Pacific history." Journal of Pacific History 1#1 (1966): 5–21.

- Dickson, Henry Newton (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 434–441.

- Dirlik, Arif. "The Asia-Pacific Idea: Reality and Representation in the Invention of a Regional Structure", Journal of World History 3#1 (1992): 55–79.

- Dixon, Chris, and David Drakakis-Smith. "The Pacific Asian Region: Myth or Reality?" Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 77#@ (1995): 75+

- Dodge, Ernest S. New England and the South Seas (Harvard UP, 1965).

- Flynn, Dennis O., Arturo Giráldez, and James Sobredo, eds. Studies in Pacific History: Economics, Politics, and Migration (Ashgate, 2002).

- Gulliver, Katrina. "Finding the Pacific world." Journal of World History 22#1 (2011): 83–100. online

- Korhonen, Pekka. "The Pacific Age in World History", Journal of World History 7#1 (1996): 41–70.

- Munro, Doug. The Ivory Tower and Beyond: Participant Historians of the Pacific (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009).

- "Recent Literature in Discovery History." Terrae Incognitae, annual feature in January issue since 1979; comprehensive listing of new books and articles.

- Routledge, David. "Pacific history as seen from the Pacific Islands." Pacific Studies 8#2 (1985): 81+ online

- Samson, Jane. "Pacific/Oceanic History" in Kelly Boyd, ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing vol 2. Taylor & Francis. pp. 901–902. ISBN 978-1-884964-33-6.

- Stillman, Amy Ku'uleialoha. "Pacific-ing Asian Pacific American History", Journal of Asian American Studies 7#3 (2004): 241–270.

External links

[edit]- EPIC Pacific Ocean Data Collection Viewable on-line collection of observational data

- NOAA In-situ Ocean Data Viewer plot and download ocean observations

- NOAA PMEL Argo profiling floats Realtime Pacific Ocean data

- NOAA TAO El Niño data Realtime Pacific Ocean El Niño buoy data

- NOAA Ocean Surface Current Analyses – Realtime (OSCAR) Near-realtime Pacific Ocean Surface Currents derived from satellite altimeter and scatterometer data

![Maris Pacifici by Ortelius (1589). One of the first printed maps to show the Pacific Ocean[38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4e/Ortelius_-_Maris_Pacifici_1589.jpg/260px-Ortelius_-_Maris_Pacifici_1589.jpg)